Sharing History: Border Monument 122

Back to our VisitTubac.com home page.

by Richard A. Zidonis

WebZar.com, Inc. Contact Rich

|

I try to imagine it's 1854, the year the U. S. Senate ratified the Gadsden Treaty. I would be on horseback, then, and Nogales would be a day's ride.

Put my Blazer 4x4 on a forest service road in the Santa Rita Mountains along the Santa Cruz Valley, and I instantly transform into an Arizona Territory pioneer, expecting a nomadic Apache warrior to rise up from the next arroyo. But pioneer I am not. I understand that the Wild West is, well, history. The year is 2010, and I am merely a snow bird tourist who occasionally thinks himself to be an adventurer.

One would assume, though, that in 1864, almost 150 years ago, the phrase "a tourist" could not attach itself to anyone giving Southern Arizona a go. Yet J. Ross Browne uttered those words.

In his book "A Tour Through Arizona - 1864," Browne writes that he "should have risen to the dignity of an original explorer, instead of rambling over the trodden paths of the western world as I now do, a mere every-day tourist, in the footsteps of those giant old freebooters."

J. Ross Browne really knows how to hurt a guy.

But I heal quickly, and despite Browne's stinging rebuke of my modern sense of adventure, I, we, can still allow our imagination to run free, and, as you will read, each of us can still touch the past that touched J. Ross Browne and others like him.

The Gadsden purchase, the last major territorial acquisition within the continental United States, was needed to establish a transcontinental railroad along a southern route. Ten million dollars later, the almost 30,000 square miles of present Southern Arizona, along with a sliver of New Mexico, became the property of the USA.

Properties come with borders, and borders need to be surveyed. West Point graduate Major William H. Emory left his mark on the Southern Arizona border within reach of each of us. In 1855, when Emory departed his Boundary Headquarters at the Grove of Walnuts - also known as Nogales, he left behind a pyramid of stones known as boundary monument 26.

When that "every-day" tourist Browne passed through the border area, he wrote first about how pleasant was the boundary area of Southern Arizona with "grass up to our horses' shoulders." He tells us also how he, "stopped awhile at the boundary line to examine the monument erected by Colonel Emory nine years earlier in 1855." He was referring to boundary monument 26, and he added that "very little of it remains save an unshapely pile of stones."

Unshapely or not, the stones were the border, and the border brought men who were busy being men. The Grove of Walnuts slowly turned into two towns, Ambos Nogales, and, as is always the case, there was money to be made.

Nogales' first permanent resident, John Brickwood, built his Exchange Saloon around boundary monument 26. His saloon became a not-so-modern version of a border crossing. Jane Eppinga writes in her book "Nogales: Life and Times on the Frontier," that a fugitive could "stop in the Exchange Saloon on the United States side, fortify himself with a glass of red-eye, and sneak out the back door into Mexico," and away from the threat of arrest or prosecution. And so went the border that was marked by a pile of rocks.

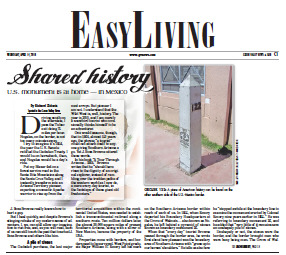

Then, almost 40 years after Emory's survey, the Boundary Resurvey of 1891 to 1894 brought an end to pyramid 26. As Border Commissioner John Whitney Barlow resurveyed through Nogales, he tore down a wall at Brickwood's Exchange Saloon, a wall that surrounded that jumbled pile of stones, and he replaced the stones with what is now known as boundary monument 122, a four-sided, cast-iron, pointed obelisk that informed in English and Spanish that you were viewing the boundary of the United States and Mexico as established by the treaty of 1853 and reestablished by the treaties of 1882-1889.

When Brickwood's Exchange Saloon was raised in 1897, boundary monument 122, for the first time since replacing monument 26, stood away from walls and buildings, with a clear view of the peoples of two nations.

When Brickwood's Exchange Saloon was raised in 1897, boundary monument 122, for the first time since replacing monument 26, stood away from walls and buildings, with a clear view of the peoples of two nations.

But that was then, and this is now. Does Barlow's obelisk still exist in 2010?

I parked my trusty 4x4 near the DeConcini Port of Entry, thrilled by the chance to find obelisk 122, but my walking inspection along the border provided no monument and no clues. Why? What was I missing?

An email to and from Brian Levin, Public Affairs Liaison for the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency, directed me to Mario Escalante, a spokesman for the Border Patrol's Tucson Sector. A telephone call to Mr. Escalante resulted in a promise to provide information, and Mr. Escalante did not disappoint. His follow-up email detailed the exact location of boundary monument 122... except it wasn't there.

With Mr. Escalante's email in hand, I walked the border through the town of Nogales, Arizona. I found no monument. I found no clue of a monument. With a sense of despair, I approached a group of Border Patrol agents. After I explained my quest and showed my email, a young woman answered. She knew! And she simply walked me to the border fence, not six feet from where we talked, and she pointed. There it was! Border Obelisk 122 was in plain sight... in Mexico.

I quickly passed through the Morley Street pedestrian crossing into Mexico, and as I approached the monument, I was instantly transported. I was no longer a man standing alone. Major William H. Emory stood there with me, as did J. Ross Browne, and both of those fine men joined me in a toast to John Brickwood and his Exchange Saloon. We watched together as Border Commissioner John Whitney Barlow removed the honored pile of rocks known as monument 26. Then, each of us quietly studied Barlow's demeanor as he created the foundation for - then placed, Obelisk 122. It was 1855, and it was 2010, and for a mere, everyday tourist, it was a fine day to be alive.